Adapting the Education Marginalisation Framework to understand gender and inclusion related barriers in the teaching profession in South Asia

Introduction

Gender Transformative Education ‘seeks to utilise all parts of an education system – from policies to pedagogies to community engagement – to transform stereotypes, attitudes, norms and practices by challenging power relations, rethinking gender norms and binaries, and raising critical consciousness about the root causes of inequality and systems of oppression’ (UNICEF, 2021). To coincide with the Global Feminist Coalition for Gender Transformative Education on the 20th and 21st September 2022, in New York, we’d like to share some key insights from our recent work with supporting and enhancing the British Council’s education programming in South Asia.

Overview

Earlier this year, Kore Global undertook a gender analysis of the education sector in South Asia to inform the British Council’s education-focused programming in the region. Through desk-based research coupled with interviews with key experts in the field, we were able to gather rich data and evidence on the dynamics of gender and the education sector in five key countries: Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Our analysis explored gender equality in the education system both from the perspective of students and their access to education and learning, as well as gender and inclusion-related dynamics in the teaching profession.

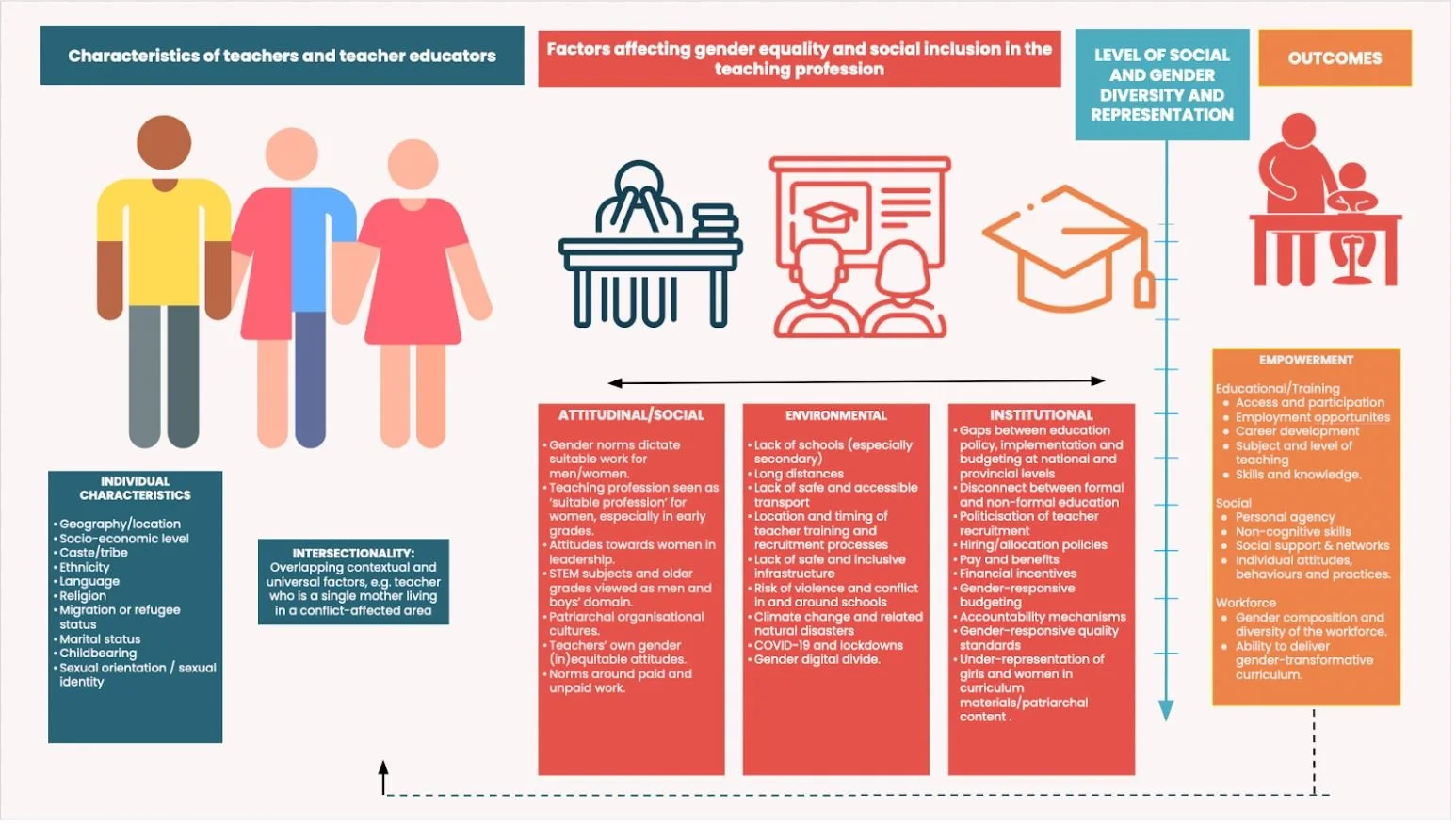

To do this, we adapted an Educational Marginalisation Framework, developed originally by the UK FCDO’s Girls’ Education Challenge Fund, to explore barriers and enablers to gender equality in the education system. We were interested to see how the framework might be adapted to look at gender and inclusion related barriers and enablers within the teaching profession itself.

This rights-based framework was originally designed to encourage analysis of attitudinal, environmental, and institutional barriers to inclusive education. And, importantly, how these barriers overlap and combine to affect girls’ and boys’ educational outcomes depending on their unique individual characteristics, such as gender, age, geography and disability status etc. By adapting the framework to be applied to the teaching profession, we hoped we could shed light on factors affecting the diversity and social inclusion (or lack thereof) within the teaching profession in South Asia, and what the overall outcomes of this are for schools, education programmes and education systems. Figure 1 presents our adapted framework.

Figure 1: Adapted educational marginalisation framework focused on the teaching profession (Adapted from GEC, 2018)

Key findings

Four key findings emerged from our use of this adapted framework:

The Education Marginalisation Framework can be adapted easily to explore the experience of teachers and teacher educators in different country contexts. It could therefore be used as a useful planning tool, to enable education practitioners to define target groups of teachers and teacher educators and analyse the various barriers which they face both entering and progressing within the profession.

To create a more diverse and inclusive education system, education programmes, systems and local provision should respond to the barriers at multiple levels faced by different groups of teachers and teacher educators.

Teachers and teacher educators can be powerful actors and allies in the fight against gender inequalities, but they can also perpetuate gender inequality in schools, systems and societies. This highlights the need for focused work with teachers at the attitudinal and social level of the framework.

While many of the barriers that women and girls face are similar, the ways in which discriminatory gender norms permeate policies, schools, and wider institutions differ across contexts, and are often shaped by the broader social, political and economic fabrics of each South Asian country.

By applying the adapted framework, we were able to highlight significant attitudinal, environmental and institutional factors affecting the teaching profession in South Asia. The ways in which these barriers combine to influence individual teachers’ experiences within the profession are closely linked to gender coupled with characteristics such as age, class/caste/ethnicity, socio-economic level, relationship status, geography, disability status and sexuality.

Across countries, we found that many of the barriers to student access, retention and learning are the same factors holding teachers back from participating and progressing within the teaching profession. For example, environmental barriers including long distances and lack of access to safe transport, conflict, and limited WASH facilities, hinder women teachers’ opportunities, while natural disasters exacerbated by climate change often have a disproportionate impact on women and girls. Similarly, gender dynamics surrounding access to digital educational resources and online training opportunities hinder teachers’ ability to provide gender-inclusive and quality teaching and learning, a situation exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns. Social and gender norms around women’s mobility, at the extreme, can limit women from engaging in any form of paid employment, and across the board affect women teachers' ability to participate in centralised and residential teacher training. In the absence of family-friendly policies, including maternity leave and free quality childcare provision, female teachers who are also wives and mothers are unable to leave their homes and domestic responsibilities, causing them to miss out on important professional development and/or leadership opportunities.

At the same time, discriminatory gender norms shape how teachers, schools and educational institutions treat their students and colleagues, highlighting the need for programmes to engage in individual attitudes and norms of teachers. Gendered perceptions around women as ‘motherly figures’ or the idea that ‘men make better leaders, researchers, scientists, or engineers,’ create an environment in which women make up the majority of the teacher population in the early grades, but then become under-represented at the post-primary grades, STEM subjects, and positions of leadership. Furthermore, pervasive patriarchal organisational cultures within national education systems can hinder progress, as policy-level decisions are often made without consultation with or participation from women themselves. While underresearched, these male-dominated cultures can lead to risks of sexual harassment and abuse, with teachers having little recourse to report instances of abuse.

Our key findings have important implications for those engaged in educational programming and highlight the importance of analysis and action to address gender and inclusion related barriers in the teaching profession. This analysis, and actions grounded in it, are what is needed, to deliver truly gender transformative education.

Written by Jenny Holden, Principal Consultant, and Sophia D’Angelo, Associate, Kore Global.

To note, that the Education Marginalisation Framework distinguishes between ‘universal characteristics’ such as age, gender, disability, and ‘contextual characteristics’ such as geography, poverty, childbearing status. For simplification, we had merged these two categories within our adapted framework.

Kore Global worked together with the British Council to develop a Resource Pack for schools on Climate Change and Girls’ Education.